Tattoos are permanent, often complex, creative, and original pieces of work created by a tattoo artist. Recently, litigation has come up regarding tattoos on famous athletes. While most issues involving tattoos on athletes are more easily handled — such as J.R. Smith’s tattoo of the brand Supreme on his leg1 — there are questions of whether a tattoo is subject to copyright protection when it is prominently displayed and reproduced on a famous athlete in a video game. This question is at the center of a lawsuit filed by Solid Oak Sketches against Take Two Interactive Software as well as two other producers of the popular NBA 2K video games based on the video games’ reproductions of players’ tattoos, including LeBron James.2

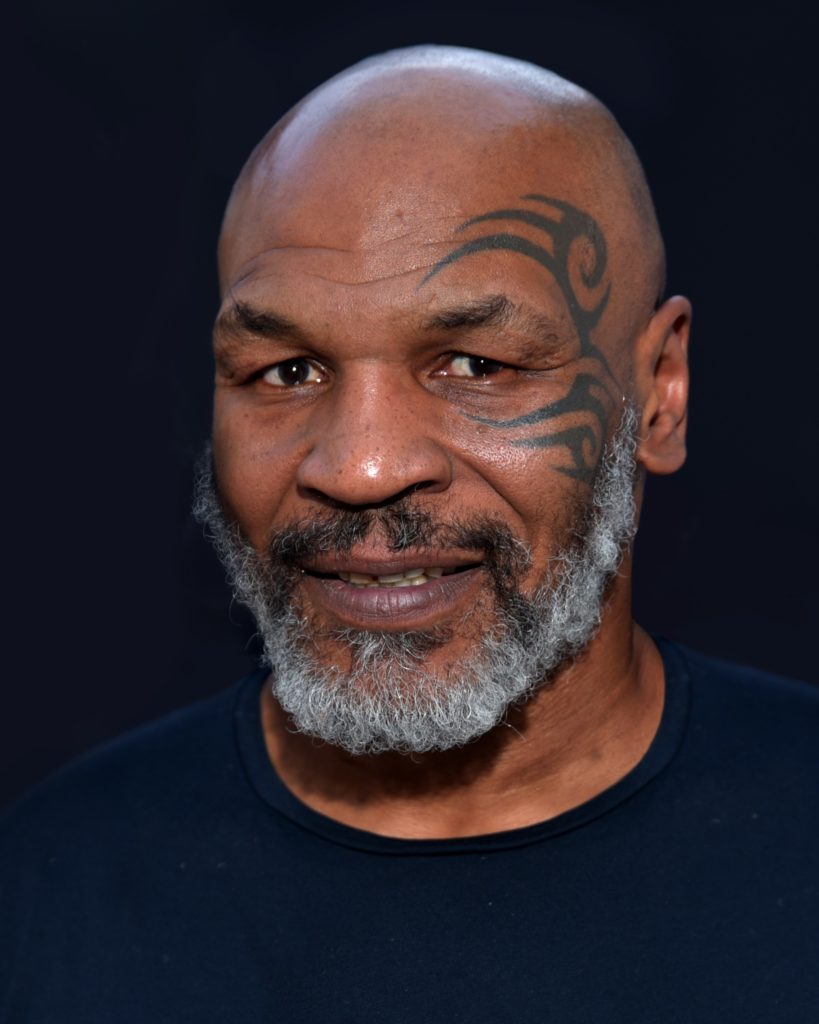

A similar issue arose in 2011, in which tattoo artist S. Victor Whitmill claimed to have copyright ownership of Mike Tyson’s face tattoo, with the tattoo in question given to Tyson in 20033. Whitmill sued Warner Bros., claiming that the popular film Hangover 2 infringed on his work when they reproduced Tyson’s tattoo on a main character’s face4. While Whitmill’s complaint failed to temporarily enjoin the studio from releasing the film in theaters, the case was settled out of court and now leaves an underwhelming amount of case law on the subject.5

The Copyright Act of 1976 gives protection to artists that establish that: (1) their creation is the type of work that is protectable; (2) their creation is an original and creative work; and (3) the creation is affixed to a tangible medium for expression.6 Further, § 202 of the Copyright Act states that “ownership of a copyright… is distinct from ownership of any material object in which the work is embodied.”7 This means that a tattoo artist does in fact have copyright ownership over original and creative tattoos that they give, even when those tattoos are on another person’s body. However, there is an implied license that allows people to freely and publicly display their tattoos — for example, on television, film, and magazines — so for most people, this is not a problem. 8However, this issue has arisen because LeBron’s tattoos are not only being displayed, but they are being digitally reproduced in a video game, causing an issue for copyright infringement issue.9

The company Solid Oak Sketches obtained the copyrights for two of LeBron James’ four tattoos in question — the portrait of his child and the area code — before suing in 2016 because they were used in the NBA 2K series.10 Take Two argues a fair use defense, stating that the tattoos are covered under fair use and are not a critical component of the video games, seen only fleetingly or rarely.11 However, that argument may not hold water due to the time and energy put into recreating both the athletes and tattoos with incredible accuracy.12 Further, this argument did not survive the motion to dismiss, with Judge Laura Taylor Swain finding that the defenses presented by Take Two are fact-intensive and will require more evidence.13

New York University intellectual property law professor Christopher Jon Sprigman says to the New York Times that Solid Oak’s lawsuit “amounts to a shakedown and copyright trolling,” stating further that “[t]hey shouldn’t be allowed to tell LeBron James that he can’t take deals to license his likeness… the ability of the celebrity, or really anyone, to do that is an element of their personal freedom.”14 LeBron James states that his tattoos are a part of his “persona and identity,” saying that if he is not shown with his tattoos, it would not be an accurate depiction of himself.15 In a Declaration of Support for the defendants from LeBron James, he states that the four tattoos in question were “inked in Akron, Ohio,” and in each case, he had a conversation with the tattooist about what he wanted inked on his body. 16

The outcome of this case will set an important precedent on whether or not tattoo artists can demand monetary compensation every time a celebrity’s likeness has been reproduced. Since the rise of litigation, players’ unions and sports agents have been advising athletes to secure licensing agreements before they get tattooed, in order to protect their future interests.17 This way, the athletes have secured their rights while giving artists have an incentive to sign rather than pass up a celebrity client who could be a walking advertisement for their art18.

1 Cam Wolf, NBA Tells J.R. Smith to Cover Up His Supreme Tattoo Or Else, GQ (Oct. 1, 2018), https://www.gq.com/story/jr-smith-supreme-tattoo-nba?verso=true (in which Cleveland Cavaliers’ J.R. Smith was told by the National Basketball Association that they would fine him for every game of the season that he failed to cover up the Supreme logo on his leg, citing the League’s Collective Bargaining Agreement, which states that ‘a player may not, during any game, display any commercial, promotional, or charitable name, mark, logo, or other identification… on his body.’).

2 Jason M. Bailey, Athletes Don’t Own Their Tattoos. That’s a Problem for Video Game Developers, New York Times (Dec. 27, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/27/style/tattoos-video-games.html.

3 Christie D’Zurilla, ‘Hangover 2’ Tattoo Lawsuit Over Mike Tyseon-style Ink is Settled, Los Angeles Times (June 22, 2011), https://latimesblogs.latimes.com/gossip/2011/06/hangover-tattoo-dispute-ed-helms-hangover-2-tattoo.html.

4 Id.

5 Id.

6 1976 General Revision of Copyright Law, Pub. L. No. 94-553, 90 Stat. 2541.

7 17 U.S.C. § 202.

8 Jason M. Bailey, Athletes Don’t Own Their Tattoos. That’s a Problem for Video Game Developers, New York Times (Dec. 27, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/27/style/tattoos-video-games.html.

9 Id.

10 Id.

11 Bryan Wiedey, Tattoos in Sports Video Games Face Legal Issue, Sporting News (Oct. 19, 2018), http://www.sportingnews.com/us/other-sports/news/madden-lawsuit-over-tattoos-nba-2k-lebron-james-ea-sports-2k-sports/16xvqkb1d2hbm1lzs6u3iljaap.

12 Id.

13 Thomas Baker, NBA 2K Tattoo Copyright Suit Offers Two Compelling Legal Arguments, but Only One Seems Practical, Forbes (Jan. 4, 2019), https://www.forbes.com/sites/thomasbaker/2019/01/04/lebron-smartly-sides-with-the-producers-of-nba-2k-in-tattoo-copyright-case-but-will-that-be-enough/#4e08f33c7663.

14 Jason M. Bailey, Athletes Don’t Own Their Tattoos. That’s a Problem for Video Game Developers, New York Times (Dec. 27, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/27/style/tattoos-video-games.html.

15 Solid Oak Sketches, LLC v. 2K Games, Inc. and Take-Two Interactive Software, 1:16-cv-00724, ECF No. 134 (Aug. 24, 2018). (Found at https://www.scribd.com/document/386980896/2018-08-24-Declaration-dckt-134-0#from_embed).

16 Id., at 1.

17 Jason M. Bailey, Athletes Don’t Own Their Tattoos. That’s a Problem for Video Game Developers, New York Times (Dec. 27, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/27/style/tattoos-video-games.html.

18 Id.

Jay

In a landmark decision in March of 2020, federal judge Laura Taylor Swain ruled that Take Two Interactive Software’s reproduction of Lebron James’ tattoos was fair use and does not infringe on Solid Oak Sketches’ copyrights. Solid Oak Sketches, LLC v. 2K Games, Inc., 449 F. Supp. 3d 333, 353 (S.D.N.Y. 2020). Because the balance of fairness is extremely fact-sensitive, it must be analyzed on a case by case basis. Evaluation of a fair use defense does not hinge on a bright-line rule but is an exploration of four factors: (1) the purpose and character of the use; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality used; and (4) the effect upon the potential market. Though some may carry more weight than others, each of these factors must be considered. First, the court held that Take Two transformed the tattoos by using them to help identify and recognize players, rather than the original purpose of player self-expression. Id. at 347. The tattoos also only comprised 0.000286% to 0.000431% of total game data. Id. at 348. Even though the tattoos were used for a commercial video game, the tattoos were not featured in marketing material and were inconsequential to the game’s commercial value. Id. at 349. The court determined that the second factor also favored Take Two because the tattoos featured common motifs copied from designs and pictures not created by the plaintiff. Id. The court found that factor three also favored Take Two because it needed to duplicate the tattoos entirely to accurately depict players. Id. at 347. Finally, the court determined that factor four favored Take Two as well because the tattoos in the game “cannot serve as substitutes for use of the Tattoo designs in any other medium.” Id. at 349. After weighing all the factors, the court granted summary judgment to Take Two. I agree with the court’s conclusion because it gives athletes’ control of their bodies. I believe that it is fair for tattoo clients to profit over their bodies, rather than a tattoo artist who has already been paid for their services.

Xinyi

So far, the courts have had no problem ruling that the tattoo art design itself is copyrightable and consumes the full scope of protection under copyright law as other copyrightable subject matters. See Tattoo Art, Inc. v. TAT Int’l LLC, 498 Fed. Appx. 341 (4th Cir. 2012) (deciding that a licensee of tattoo art designs infringed the licensor’s copyrights by displaying altered versions of the designs on a website and by continuing to display the designs after the license was terminated.) However, the courts still resist holding that the tattoos on the human body are also copyrightable. See Solid Oak Sketches, LLC v. 2K Games, Inc., 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 53287 (S.D.N.Y. March 26, 2020).

In Solid Oak Sketches, LLC, the Southern District Court of New York (“The Court”) ruled for the defendant, 2K Games, Inc (“2K”), by granting its motion for summary judgment. In this case, the plaintiff, Solid Oak Sketches, LLC (“SOS”), alleged that 2K had infringed its copyrights by publicly displaying the five tattoos (“The Tattoos”) depicted on NBA players Eric Bledsoe, LeBron James, and Kenyon Martin (“The Players”) in various versions of 2K’s basketball simulation video game.

The Court firstly determined that SOS failed to establish a claim of copyright infringement because 2K’s use of The Tattoos is de minimis use and thus not sufficient to satisfy the substantial similarity element of copyright infringement. The Court lists out three quantitative components to determine de minimis use: (1) the amount of the copyrighted work, (2) the observability of the copied work, and (3) factors such as “focus, lighting, camera angles, and prominence.” Solid Oak Sketches, LLC, at 16. There the court held that 2K’s usage is de minimis because The Tattoo only appeared on three out of over 400 available players in its games; The Tattoos were not featured on any of the game’s marketing materials; and the Tattoo could not be identified or observed given its significantly reduced size. It is considered clear that 2K’s video games did not emphasize the presence of The Tattoos but merely included them to simulate the realistic feeling of the game. However, 2K’s usage of The Tattoos is more like a typical example of de minimis use, since The Tattoos were not used to feature the whole game but merely considered incidental by The Court.

The Court further decided that an implied non-exclusive license was created when the tattoo artists inked The Tattoos on to the Players’ skin per the Players’ request of creation and with the intention to let the Players to copy and distribute the Tattoos as elements of their likeness. With the implied non-exclusive license, The Players either directly or indirectly granted 2K a license to use their likeness. If inking tattoo on the human body is equivalent to granting an implied non-exclusive license, tattoos on the human body are almost impossible to be copyrighted.

Lastly, The Court ruled that the 2K’s usage of The Tattoos are considered as fair use since the usage was transformative based on its clear difference of the purposes between the copied tattoo designs and the video game. In addition, The Court admitted that 2K’s usage of The Tattoos were commercial in nature, it was still considered as fair use since the usage was incidental to the commercial value of the game and would in no way constitute a substitute of the Tattoo design, which could, in turn, harm the commercial value of the tattoo design. The Court’s analysis here actually echoes its reasoning of de minimis use to some extent, since The Court weighs on the fact that the usage of The Tattoos are not the dispositive feature to the game.

According to Solid Oak Sketches, LLC, the courts’ attitude towards copyrighting tattoos on the human body still seems to remain reluctant. If the tattoo artists really want to claim their rights on the tattoo design inked on their customers’ bodies, it seems that the only way for them is to sign a separate contract with their clients to limit the client’s usage of the tattoos as elements of their likeness.

Jordan

Tattoos are artistic expressions created by talented individuals. They take time, patience, precision, and creativity to complete so it is understandable why tattoo artists are not happy when witnessing their life’s work depicted in movies and video games without being compensated or giving permission for the use. While Courts have acknowledged that tattoo art is copyrightable and deserve the full protection of the Copyright Act, they have been reluctant to rule that tattoos depicted on the human body in a digital medium (such as in video games) is copyrightable. Those who are alleged to have infringed on the the artist’s copyrightable work have all plead similar affirmative defenses of implied license, fair use, and de minimus use. See Alexander v. Take-Two Interactive Software, F.Supp.3d, 3-6 (S.D.Ill 2020).

Normally Copyright owners hold the exclusive right to copy or distribute their work as they see fit. Id. at 6. They can authorize the use of their work through exclusive written licenses or an implied one. Id. In an implied license the Copyright owner does not transfer ownership in their work to the licensee, rather it permits the use of a work in a particular manner. In order for an implied license to exist: “(1) a person (the licensee) request the creation of the work, (2) the creator (licensor) creates that particular work and delivers it to the licensee, (3) the licensee intends that the licensor copy and distribute their work.” In instances like these where large gaming companies are using the likeness of these big time sports players, many courts have found that these tattoo artist granted an implied license to the players to use as a part of their likeness (licensors) because once the artist puts their work on these public figures these artist know that the players are likely to appear in public, on television and other forms of media. Since these tattoos are apart of the players likeness, once they license out their likeness to these companies they are also granting permission to use their tattoos in whatever media form they see fit. Many courts have applied the de minimus defense to these cases in which the copyrighted work used is so trivial that the use would not amount to an infringement. With video games requiring so much data for their completion, the display of certain tattoos on players bodies that have already been licensed out amounts to such a small percentage of data as compared to what’s needed for the entire game, that no one is really truly harmed. I agree with the courts recent decisions on these matters because it gives players more control over what to do with their bodies. Not to mention that these basketball players most likely pay a huge sum of money to get these tattoos done, they should at least have the final say so on their bodies.

Craig

It is interesting to note that Take Two Interactive was involved in another copyright infringement case regarding the depiction of athletes in their video games. In Alexander v. Take-Two Interactive Software, the plaintiff tattoo artist filed a copyright infringement suit in the Southern District of Illinois against Take-Two Interactive and World Wrestling Entertainment over the depiction of WWE wrestler Randy Orton in the WWE 2K video games. Similarly to Solid Oak Sketches, Take-Two had replicated Orton’s likeness by digitally reproducing his tattoos that were inked by plaintiff for use in their video games.

In that case, the defendants filed for summary judgment, arguing that Take-Two’s recreation of the tattoos in the video games was authorized by an implied license, that the depiction of Orton’s tattoos in the games were protected by the fair use doctrine, and that the tattoos were a de minimis part of WWE 2K. Unlike the Southern District of New York in Solid Oak Sketches, however, the Southern District of Illinois in Alexander denied defendants’ motion.

The Court rejected defendants’ implied license affirmative defense, finding that it was unclear as to whether Alexander and Orton had ever discussed copying and distributing the tattoos. This was an issue of fact for the jury to decide. In Solid Oak Sketches, the Court found there was an implied license, as the tattoo artists stated their intent to have their art become part of the player’s likeness and persona in the public and other forms of media. It is interesting to ponder why this same logic would not apply to Alexander, especially given the scripted nature of professional wrestling. Professional wrestlers, unlike athletes in real sports, technically play characters when they perform on television. Wouldn’t the tattoos be a part of the likeness of not only Randy Orton the human being, but also Randy Orton the character that he portrays on television that was created and owned by WWE?

The Court rejected defendants’ claim of fair use, stating that there were triable issues of fact as to whether the use of the tattoos in the video games were transformative, or if their use had the same purpose. Yet in Solid Oak Sketches, the court recognized that defendants’ use of the tattoos was transformative because the purpose was to create a realistic depiction of the players, which is a different use from the tattoos from the plaintiff. As graphics improve, there are greater expectations from gamers that video game developers recreate athletes as realistically as possible. Are factors like market expectations enough for courts to find recreating an athlete’s tattoos a fair use?

The Court rejected defendants’ claim that the tattoos were a de minimis part of WWE 2K, finding that the de minimis is successfully invoked in cases where there was a small and insignificant portion copied, and not a wholesale copying of works as occurred here. In Solid Oak Sketches, the Court found that the tattoos were a de minimis part of the NBA 2K games, as the game included over 400 players, and that the tattoos were too small and obstructed by in-game elements to be noticed by a reasonable observer.

The different findings in these two cases surrounding Take-Two Interactive’s games highlight the grey areas of copyright law in the art form of video games. As video games become more realistic, courts will have to consider not only the legal implications, but practical aspects as well, including the genre and nature of the video game, as well as market demands from modern day gamers.

Ben

Tattoos are arguably one of the most permanent ways to express one’s individuality. Yet, tattoos and tattoo culture as a whole never seem to stray too far from controversy. Despite a more widespread acceptance of tattoos in modern business culture and society at large, there is still much debate over the legal rights of tattoo artists, the tattoos themselves as pieces of art, and those who adorn them. Solid Oak Sketches, LLC v. 2K Games, Inc. addresses the bulkhead of these controversies and attempts to resolve the most elusive issues therein.

The court ultimately ruled that the use of Lebron James’ tattoos in 2K Games’ video game is de minimis and an agreeable utilization of the fair use defense, and therefore did not violate Solid Oak Sketches’ copyrights. This ruling represents a huge win for the rights of tattooed athletes, celebrities, and public figures, and a successful fight for civil liberties as a whole. While it has been well established that the Copyright Act of 1976 gives tattoo artists protection over their original and creative artwork, I believe the issue in 2K Games misinterprets the idea of what tattoos are at their core. It can be argued that tattoos belong as much to the artists as they do their human canvases – surely, a painter still retains property rights to their art despite transferring it from brush to canvas. But different mediums of art require different analyses– especially those that include the transfer of art that involves permanent physical alteration. Here is where I believe tattoos belong more to the individual than the artist unless someone is specifically using an individual and unique tattoo to promote a more tangible or attributable benefit, as The Hangover 2 did with Mike Tyson’s infamous face tattoo for shock value and notoriety. The reasoning of the court here expresses this view in their decision, ruling in favor of James and 2K Games. 2K Games used James’ tattoos not in a way to profit from them, but to profit off the advanced graphics and realistic portrayal of NBA players in their new game. The portrayal of these tattoos does not advance any selling point as it relates to the tattoos themselves, but to the advanced gameplay and faithful aesthetic representation of basketball and its players.

Further, there does not seem to be any practical way to assess any alleged damages suffered by Solid Oak Sketches as a result of 2K’s portrayal of James’ tattoos. Injunctive relief seems equally inapplicable and troublesome, as it would further challenge the integrity of James’ persona and the game as a whole.

In 2022, it is increasingly difficult to dismiss the legal issues surrounding tattoos. They are almost as common a body modification in today’s world as ear piercings, and are becoming more allowable in even the most conservative work and public spaces. Tattoo artists and wearers have more power than ever to assert their legal rights and artistic freedoms. It is the job of the judicial system and legal scholars to address these issues with the same tenacity as any other, distinguishing between traditional and more modern, interpretive methods to solve these complex issues.

Ryan

This post addresses a very interesting area of the law, specifically, the tension between expressive rights embodied in the First Amendment and property rights embodied in right of publicity laws. Yolanda M. King, The Right-of-Publicity Challenges for Tattoo Copyrights, 16 NEV. L.J. 441, 455 (2016).

Right of publicity laws “prevent[] the unauthorized commercial use of an individual’s name, likeness or other recognizable aspects of one’s persona.” Id. at 445. Since tattoos can become part of an individual’s persona, most notably for celebrities, individuals could bring a claim if the likeness of their tattoos has been commercially exploited without authorization.

Naturally, granting tattoos protection under right of publicity laws creates a conflict with other individuals’ freedom of expression in recreating those tattoos under the First Amendment. In diffusing this tension, Courts often “weigh the state’s interest in protecting a plaintiff’s property right to the commercial value of his or her name and identity against the defendant’s right to free speech.” Id. at 455. To perform this analysis for visual aspects of an individual’s identity, courts have utilized two tests: the Transformative Use test and the Predominate Use test. Id.

The California Supreme Court developed the Transformative Use test from one of the fair use factors of federal copyright law. Id. at 456. This test considers five factors: [1] whether the depiction adds “significant expression,” [2] whether the celebrity image is one of the “raw materials from which an original work is synthesized,” [3] whether the work is “primarily the defendant’s own expression rather than the celebrity likeness,” [4] whether the “literal and imitative elements” or the “creative elements” predominate the work, and [5] whether the “marketability and economic value” of the work derives primarily from the celebrity’s fame.” Id. at 456-457. Generally, this test looks at whether the defendant “sufficiently transforms the plaintiff’s identity in the visual artistic work.” Id. at 457. This approach can be problematic however since transformativeness is a highly subjective matter.

The Supreme Court of Missouri was the first to utilize the Predominate Use test and it was adopted from Mark S. Lee’s article, Agents of Chaos: Judicial Confusion in Defining the Right of Publicity – Free Speech Interface. Id. at 462-463. Under this approach, if a product exploits the commercial value of an individual’s identity, the product violates the right of publicity and is not protected by the First Amendment, regardless of any expressive content in the product. On the other hand however, if the product’s predominant purpose is to make an expressive comment about an individual, the expressive values could be given greater weight. Id. at 463.

Under these two tests, it appears that a court would be more likely to find that an individual’s right of publicity outweighs other individuals’ expressive use in California as opposed to Missouri, since the California’s Transformative Use test is more flexible and subjective as compared to the Missouri’s Predominate Use test which is far stricter.