Background

The idea behind the concept of Net Neutrality arose in the early 2000s, when, inter alia, the High Tech Broadband Coalition (“HTBC”) filed comments before the Federal Communications Commission (“FCC”). At the time, the HTBC urged the FCC to “vigilantly monitor” the provision of internet services to consumers to ensure rights to access content of their choice.

Today the matter has, to a great extent, become a political battle largely drawn along ideological/party lines. Nonetheless, the issue remains an important one that should not be ignored, especially in today’s world where access to the internet is essential to daily personal and business life.

The regulations, put in place by the Obama administration in 2015, enshrined the principle of net neutrality in U.S. law. The basic tenet of Net Neutrality is that Internet Service Providers (“ISPs”), like ComCast, Spectrum or Verizon, should treat all internet traffic ‘traveling’ through their infrastructure to the end consumer in the same manner. Essentially, Net Neutrality ensures that these ISPs act as mere conduits to data that travel between the content provider/originator and the end consumer.

The argument for, and against, net neutrality

Some of the initial proponents of Net Neutrality were content providers, such as Amazon and Google, who put forward the view that regulation was needed to ensure broadband providers were not unfairly, or otherwise, prioritizing the internet. It was argued that such prioritization would lead to consumers receiving substandard service and experience, especially when the providers themselves were competing in the provision of similar services.

Since these initial days, the arguments for net neutrality has gained widespread support, amongst them from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). They argue that there is no guarantee the internet will remain a free and open medium should Net Neutrality be taken away. Rather, they argue, the pursuit of profit and corporate policies, may favor the monitoring and playing favorites to what individuals see on the internet and/or the quality of their connection. There were well known instances in the past where AT&T interfered by censoring a rock star’s political speech and Comcast decreasing the quality of the internet services to those who use BitTorrent programs. The ACLU also cites to an occasion where a Canadian Wireless provider, Telus, blocked its users from accessing the website of a Labor Union that was on strike against Telus.

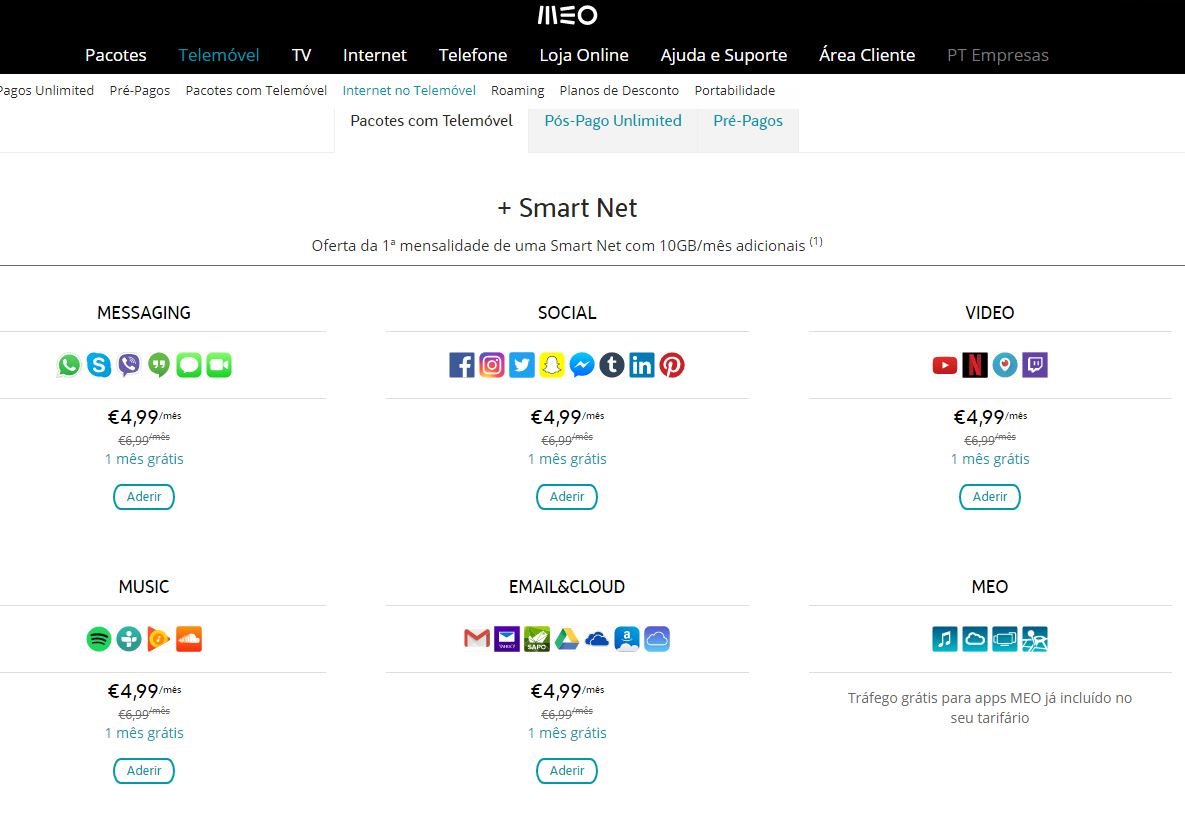

The repeal of Net Neutrality concerns are well-founded. In other jurisdictions, where net neutrality laws were not to the standard set forth by the Obama Administration, ISPs have been experimenting with plan offerings of piecemeal media and data offerings.

In Portugal, with no net neutrality, internet providers are starting to split the net into packages. In Portugal, mobile carrier MEO offers regular data packages, but it also offers, for €4.99 a month, 10GB “Smart Net” packages. One such package for video provides 10GB of data exclusively for YouTube, Netflix, Periscope and Twitch, while one for messaging bundles six apps including Skype, WhatsApp and FaceTime.

In New Zealand, Vodafone offers a similar service: for a daily, weekly, or monthly fee, users can exempt bundles of apps from their monthly cap. A “Social Pass” offers unlimited Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat and Twitter for NZ$10 for 28 days, while a “Video Pass” gives five streaming services – including Netflix but not YouTube – for $20 a month.

However, when discussing the issue of Net Neutrality, it should not be discussed without analyzing the arguments of the ISPs outside of the political prism. The reality is the provision of internet services to data hungry consumers is an expensive endeavor. Hence, the reason why common carriers, such as telecom and now internet service providers, have been traditionally allowed a natural monopoly. High entry costs and barriers to entry meant only a few large companies are able to provide a service to the end consumers. The present composition of FCC, trying to undo (or palm off the policing of the internet to the FTC) argue that since 2015, when Neutrality regulations came into force, investment in broadband infrastructure has diminished. This in-turn, they argue, would mean areas where broadband services are unavailable or less available would fall further behind in infrastructure investments as the revenue streams for the providers are harder to come by.

Conclusion

Thus, it is clear that the debate about Net Neutrality is a serious and could decide the future of America’s superhighway. Decisions on such a wide ranging and important subject matter should be taken after careful consultations with all parties concerned and devoid of the toxic political climate. This issue, effectively, if not decided properly has the potential to adversely affect America’s edge in innovation and competition. The vote is planned for Thursday, December 14, 2017 and the net neutrality repeal proposal is expected to pass along party lines.

Gabriel

Currently, the vote in the FCC is 3-2 in favor of repealing the rules of Net Neutrality. As we press on to the future, especially with respect to technology, it appears the FCC is trying to move us all backwards. In an era, in which virtually every hand of every citizen there is a mobile phone with internet connection, and can use it to make payments, purchase goods and medicines, check the video surveillance of his front yard, check the scores of your team, connect with your family abroad, and whatever the future comes up with, we have been given the news that in the United States of America, the concept of net neutrality is about to be dismissed.

Once the rules are repealed, broadband providers will start to limit what you can access on the web and what you can’t. And if your ISP competes with, for example, Netflix, then your ISP has the entire liberty to block/throttle your access to it, or to charge you more if you want to watch movies on Netflix, rather than watching movies on the ISP’s website for the same price.

It appears that the death of net neutrality will create an environment, and likely financially incentivize, ISPs to discriminate what price to charge the users, depending on what the users’ decisions. Several arguments are made in favor of giving the ISPs this freedom, and one such reason is that the customer that chooses to use the internet for certain purposes should pay accordingly, and other users that do not stream videos should pay less. But then again, who will have the power to discriminate the users? The same internet providers? Why should the ISPs hold the power to tell the user what to see according to platform, and at potentially fluctuating access and price points?

• Anti-trust Analogy: the Robinson-Patman Act

Although it can be debated that it does not apply to this case –in essence the Robinson-Patman Act applies to commodities, but not to services—I believe that the internet has really become a commodity, which according to Merriam-Webster’s dictionary is defined as: “an economic good such as a mass-produced unspecialized product”; or, “a good or service whose wide availability typically leads to smaller profit margins and diminishes the importance of factors other than price.” Black’s Law Dictionary defines commodity as “[a] good that is sold freely to the public,” which the internet right now, is.

According to the Federal Trade Commission, the institution who protects America’s consumers, “[a] seller charging competing buyers different prices for the same “commodity” … may be violating the Robinson-Patman Act.” In the present case, the “commodity” is the internet, and what the user does with it should not be singled out and discriminated into certain groups, for which the ISPs can charge more, or less. Is the price difference justified by different costs in manufacture or sale? The past four years prove it is not, therefore, Net Neutrality ought not be repealed, instead, such rules must be enforced.

• Legal Battle to Save Net Neutrality

Such controversial decision has made way to the Senate, where Democrats are trying to force a vote on a simple repeal of the FCC’s repeal, in which the proposal will need 51 votes to win, since Vice President Mike Pence could break any tie. Senate Democrats would need at least two Republican Senators to vote along. However, if there is majority in the Senate, the repeal would also require a win in the House of Representatives, where Republicans hold the majority, decision that could also be subject to a veto by President Trump.

State lawmakers are also making an effort to protect net-neutrality. Bills have been introduced in Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, and five other States forbidding ISPs from blocking, limiting or interfering with customers’ internet service, obligating the ISPs to follow net-neutrality policies.

In addition, New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman filed a suit on January 16, 2018 along with 20 other State Attorney Generals and the Attorney General of the District of Columbia, against the FCC to block the rules. New York’s AG has said that the FCC made “arbitrary and capricious” changes to existing policies, and departing from the FCC’s long-standing policy of defending net-neutrality was unjustified. Mozilla Corp. (creator of the Firefox web browser), a public-interest group called Free Press, and New America’s Open Technology Institute also filed similar petitions on the same day.

The battle for net-neutrality is far from over, and as someone told me, it seems that this story has a life of its own, every morning there is something new.