-

-

-

NFTs and Trademarks: General Overview

-

Interest in blockchain technologies, cryptocurrencies, and particularly non-fungible tokens (NFTs) is steadily increasing. According to Eric Anziani, COO of Crypto.com, “NFTs really started initially with the digital art side. But it’s going to be a lot more powerful. It will be the tool that represents any digital type of assets in virtual worlds going forward. So the applications are tremendous1.”

Basically, an NFT is a (i) cryptographic on the blockchain; (ii) representing an asset; (iii) that is unique and non-interchangeable. For instance, Finzer D. describes NFTs as: “unique, digital items with blockchain-managed ownership2.” Indeed, NFTs, powered by blockchain, have unique qualities which can be applied in different industries and businesses including fine arts, gaming, digital identity, certification, licensing, etc. In this respect, the sudden economic growth of the NFT market is understandable. Businesses also tend to use NFTs as marketing tools and as a creative way for building the brand’s image.

In the meantime, the rise of the NFT market poses new legal challenges, including those in the realm of intellectual property and especially trademark law. Two main trends are worth highlighting. First, there is a significant increase of trademark filing activity around NFT brands. Second, the number of new NFT-related enforcement cases is constantly increasing, including a number of high-profile litigation cases.

-

-

Prosecution: How to Trademark your NFT and Avoid Infringing Third-Parties Trademarks

-

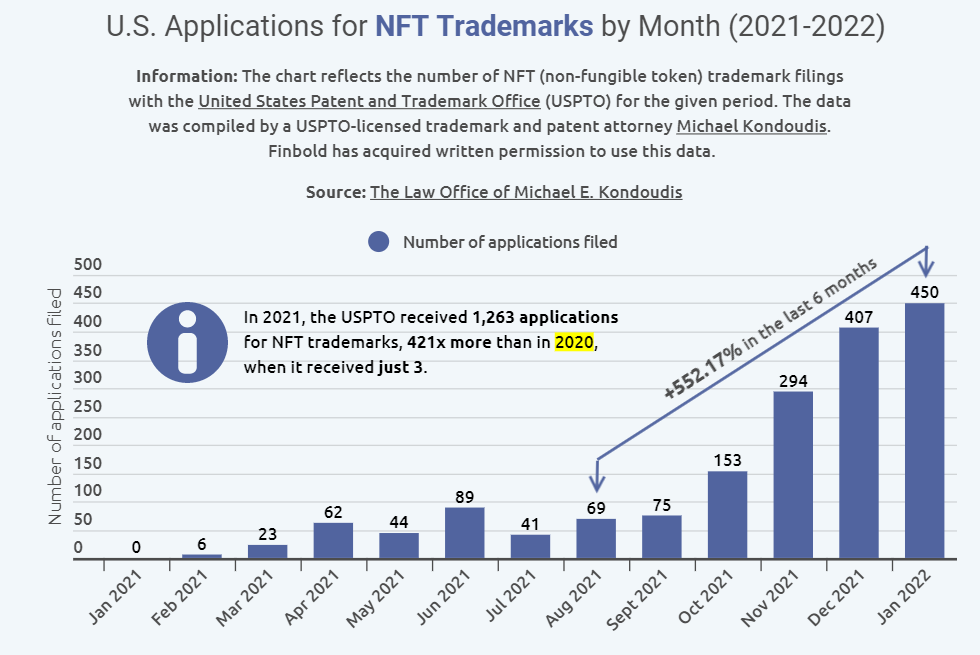

With increased media coverage and popularity, U.S. NFT trademark applications skyrocketed during the past year.

According to open sources, there was a 552% increase in NFT trademark applications with the U.S. patent agency between August 2021 and January 20223. In January alone, about 450 filings for NFT-related trademarks were received4. [Graphical representation of the data is below.]

Some of the latest examples of NFT-related trademark applications include:

NUMBERDESIGNATIONAPPLICANTFILING DATEGOODS/SERVICES97273630MONSTERMonster Energy CompanyFebruary 18, 2022IC 009 (e.g., virtual goods, software enabling users to experience virtual reality and augmented reality visualization, manipulation, and immersion…) IC 035 (e.g., retail store and online retail store services) IC 041 (entertainment services) IC 042 (providing on-line non-downloadable software; platform as a service (PaaS) and software as a service (SaaS))97261560NYSENew York Stock Exchange (NYSE Group, Inc.)February 10, 2022IC 009 (e.g., virtual goods, software enabling users to experience virtual reality and augmented reality visualization, manipulation, and immersion) IC 035 (e.g., provision of an online marketplace) IC 036 (e.g., financial exchange of virtual currency in the field of digital currency) IC 042 (e.g., computer services, electronic storage of cryptocurrency)97226848NETAVERSEBrooklyn Nets, LLCJanuary 19, 2022IC 025 (Clothing)97244783NFT StarterNFT Starter Inc.January 28, 2022IC 009 (Downloadable image files containing artwork, video clips, writings, and multimedia authenticated by non-fungible tokens (NFTs))97251874NFT BEERColumbia Craft, LLC.February 3, 2022IC 032 (Beer) IC 036 (Financial exchange of crypto assets; Financial services) IC 041 (Entertainment services)97253179 McDonald’s CorporationFebruary 04, 2022IC 043 (operating a virtual restaurant)97257474

McDonald’s CorporationFebruary 04, 2022IC 043 (operating a virtual restaurant)97257474 Victoria’s Secret Stores Brand Management, LLCFebruary 14, 2022IC 009 (e.g., downloadable virtual goods) IC 035 (e.g., retail store services featuring virtual goods) IC 041 (entertainment services)97206583L’ORÉALL’ORÉALJan. 06, 2022IC 009 (Downloadable virtual goods) IC 035 (e.g., retail store and online retail store services) IC 041 (Providing an interactive website for virtual reality game services; Entertainment services)97096366

Victoria’s Secret Stores Brand Management, LLCFebruary 14, 2022IC 009 (e.g., downloadable virtual goods) IC 035 (e.g., retail store services featuring virtual goods) IC 041 (entertainment services)97206583L’ORÉALL’ORÉALJan. 06, 2022IC 009 (Downloadable virtual goods) IC 035 (e.g., retail store and online retail store services) IC 041 (Providing an interactive website for virtual reality game services; Entertainment services)97096366 Nike, Inc.October 27, 2021IC 009 (downloadable virtual goods) IC 035 (retail store services featuring virtual goods) IC 041 (entertainment services)90602664ANDY WARHOLThe Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.March 25, 2021(Published on February 22, 2022)IC 009 (downloadable image and multimedia files containing artwork, text, audio, video, games relating to art, collectables, and Non-Fungible Tokens) IC 041 (providing on-line digital publications in the nature of blogs, articles, e-books, podcasts, and videos in the fields of art, artwork, and NFTs (non-fungible tokens) via the Internet (not downloadable)) IC 042 (e.g., providing temporary use of online non-downloadable simulation software for trading non-fungible tokens used with blockchain technology)

Nike, Inc.October 27, 2021IC 009 (downloadable virtual goods) IC 035 (retail store services featuring virtual goods) IC 041 (entertainment services)90602664ANDY WARHOLThe Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.March 25, 2021(Published on February 22, 2022)IC 009 (downloadable image and multimedia files containing artwork, text, audio, video, games relating to art, collectables, and Non-Fungible Tokens) IC 041 (providing on-line digital publications in the nature of blogs, articles, e-books, podcasts, and videos in the fields of art, artwork, and NFTs (non-fungible tokens) via the Internet (not downloadable)) IC 042 (e.g., providing temporary use of online non-downloadable simulation software for trading non-fungible tokens used with blockchain technology)Considering this increased focus on obtaining trademark protection for NFTs, it is essential to note that all general trademark registration requirements apply to NFT-related trademarks. In particular, trademarks are always registered for specific classes of goods and services (their intended use). In most cases, NFT-related trademarks are registered for the following classes:

-

-

- International Class 009 (downloadable virtual goods)

- International Class 035 (online retail store, business services)

- International Class 036 (financial, banking services)

- International Class 041 (entertainment services)

-

Trademarkers must make a preliminary assessment of what classes and services to specify, form an accurate description of services/goods involved, and analyze descriptiveness and potential consumer confusion. According to the USPTO, registering a trademark usually takes about 12-18 months.

-

-

Enforcement: Unauthorized Use of Trademarks in the NFT-based Projects

-

Obtaining a trademark registration can be essential to prohibit third parties from unauthorized use of the trademarked designations in their NFT-based projects. However, since NFTs are so new, most brands have not established comprehensive trademark protections specifically for NFT-related goods and services.

In the meantime, many NFT-based projects started to use famous trademarked brands without any consent from their owners. For example, a collection of 100 virtual versions of Hermès handbags appeared as NFTs created by Mason Rothschild at his metabirkin.com website. The name “METABIRKIN” was used for the project. This project inevitably implicated trademark rights and triggered a trademark lawsuit. On January 14, 2022, the rights holder of BIRKIN trademarks, Hermès, filed a trademark infringement and dilution lawsuit against Mason Rothschild.

According to the complaint, Hermès alleges that Rothschild is trying to “get rich quick by appropriating the brand MetaBirkins for use in creating, marketing, selling, and facilitating the exchange of digital assets known as non-fungible tokens” and “make his fortune” by swapping out Hermès’ “real life” rights for “virtual rights5.” Hermès specifically asserts the following causes of action:

-

-

-

Trademark Infringement (unauthorized use of the BIRKIN Mark resulted in Rothschild unfairly benefiting from Hermès’ advertising and promotion and profiting from Hermès’ reputation and the BIRKIN Mark).

-

False Designations of Origin (falsely or misleadingly describe and/or represent the METABIRKINS NFTs as those of Hermès)

-

Trademark Dilution (Rothschild intentionally and willfully utilized the BIRKIN Mark to trade on Hermès’ reputation and goodwill)

-

Cybersquatting (registration and use of the Infringing Domain cause consumers to falsely believe that the METABIRKINS Website and the infringing METABIRKINS NFTs are affiliated with, endorsed or approved by Hermès)

-

Injury to Business Reputation and Dilution (New York General Business Law)

-

Common Law Trademark Infringement

-

Misappropriation and Unfair Competitionunder New York Common Law

-

-

In particular, according to Hermès, the “METABIRKINS brand simply rips off Hermès’ famous BIRKIN trademark by adding the generic prefix ‘meta’ to the famous trademark BIRKIN.” At the same time, Rothschild claimed, “I’m not creating or selling fake Birkin bags. I’ve made artworks that depict imaginary, fur-covered Birkin bags6.” Rothschild appealed to First Amendment rights and the prevalent “Rogers test” which helps to determine the balance between protecting artistic expression and avoiding potential confusion with a famous mark.

Currently, multiple versions of the test exist, but a decision in this case could make applications more uniform and create a new standard for use of trademarks in expressive work. On such a possibility, Susan Scafidi, the director of Fordham University’s Fashion Law Institute, opined that “[this case] has the potential to provide guidance on how art and fashion will coexist in the digital world.”

Another relevant high-profile case is Nike, Inc. v. StockX7. Nike filed a complaint against StockX, the operator of an online resale platform for various brands of sneakers, apparel, luxury handbags, electronics, and other collectible goods that purports to provide authentication services to its customers. According to Nike, “without Nike’s authorization or approval, StockX is “minting” NFTs that prominently use Nike’s trademarks, marketing those NFTs using Nike’s goodwill, and selling those NFTs at heavily inflated prices to unsuspecting consumers who believe or are likely to believe that those “investible digital assets” (as StockX calls them) are, in fact, authorized by Nike when they are not8.”

Nike asserts the following causes of action:

-

-

-

Trademark Infringement (StockX’s unauthorized use of Nike’s Asserted Marks constitutes trademark infringement of Nike’s federally registered trademarks, which has caused damage to Nike and the substantial business and goodwill embodied in Nike’s trademarks in violation of Section 32 of the Lanham Act)

-

False Designations of Origin / Unfair Competition (StockX’s unauthorized use of Nike’s Asserted Marks and/or confusingly similar marks constitutes a false designation of origin that is likely to cause consumer confusion, mistake, or deception as to the origin, sponsorship, or approval of

-

Trademark Dilution (Nike’s Asserted Marks have become distinctive and “famous”… StockX’s use of Nike’s Asserted Marks and/or confusingly similar marks has been intentional and willful)

-

Injury to Business Reputation (New York General Business Law)

-

Common Law Trademark Infringement and Unfair Competition (that StockX acted knowingly, willfully, wantonly, oppressively, fraudulently, maliciously, and in conscious disregard of Nike’s rights).

-

-

The overlap between this lawsuit and the MetaBirkin case is apparent and StockX will likely also claim fair use and First Amendment protection.

In this respect, these cases may be landmarks which will influence future cases involving allegations of trademark infringements by NFT-based projects.

-

-

Enforcement: NFTs and Cybersquatting

-

As a related but separate issue, the recent increase in NFT-related domain name disputes has given rise to a new wave of arbitral litigation using the Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP). This is in no small part due to “cybersquatters” registering NFT-related domain names using well-known trademarks.

For instance, an UDRP dispute arose involving the domain name “nftmorganstanley.com” unrelated to the actual Morgan Stanley financial services firm9. Upon the complaint of Morgan Stanley, the UDPR panel considered the registered domain name confusingly similar to the trademark owned by the firm.

The UDRP panel found that the registrant of the nftmorganstanley.com domain name had no rights or legitimate interests in it and that the domain name was registered and used in bad faith. The panel in part determined that the use of competing pay-per-click links indicated bad faith. Due to this, the panel ordered the domain name transferred to Morgan Stanley.

WhatsApp also faces unauthorized registration of several NFT-related domain names (nftwhatsapp.click, nftwhatsapp.com, nftwhatsapp.net, whatsappnft.click, whatsappnft.com and whatsappnft.net). Such domain names were registered on the name of Turkish individuals and organizations. WhatsApp filed the respective complaint with the WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center. The Panel considered the complaint and stated the following: “The incorporation of a well-known trademark into a domain name by a registrant having no plausible explanation for doing so may be, in and of itself, an indication of bad faith10” The Panel ordered that the disputed domain names be transferred to the complainant.

From these examples, the addition of the descriptive NFT acronym does not prevent a finding of confusing similarity and subsequent transfer of a domain name to the actual trademark holder. As in all cybersquatting cases, demonstration of a lack of the registrant’s rights or legitimate interests in the disputed domain names and evidence of bad faith registration can be informative in decision-making processes.

Overall, the UDRP is a valuable instrument that can be used against “crypto-squatters” trying to capitalize on the registration of NFT-related domain names.

-

-

Conclusions and Further Implications

-

The growth of the NFT market has spurred the increase of NFT-related trademark applications as well as new trademark infringements including those brought under UDPR litigation and fair use / first amendment protections.

It seems reasonable to expect more high profile NFT-related trademark cases in the future. In addition to analyzing infringement and cybersquatting cases, we can expect NFT-related disputes in the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) as well as contracts arising from trademark licensing and assignment.

In the meantime, both right-holders and owners of NFT-based projects can mitigate their legal risks associated with the possible trademark infringements in a variety of ways. In particular, right-holders and owners can:

-

-

-

Register trademarks specifically for NFT-related goods and services

-

Register domain names with the acronym “nft.”

-

For trademark holders, monitor the use of trademarks in NFT-based projects and registration of relevant trademarks and domain names in the name of third parties. In case of potential violations, immediately take appropriate action (e.g., sending cease-and-desist letters)

-

For NFT-based projects, make a risk assessment with regards to the used designations/logos used as part of their projects

-

Carefully form and articulate enforcement/litigation strategy and respective argumentation.

-

-

-

1 NFTs: The metaverse economy. Financial Times (2022). Available at: URL: https://www.ft.com/partnercontent/crypto-com

2 Finzer D. (2021) The Non-Fungible Token Bible: Everything you need to know about NFTs. Available at: URL: https://blog.opensea.io/guides/non-fungible-tokens/

3 Sujha Sundararajan. U.S. NFT Trademark Filings Soared 400X Since 2021. Available at: https://www.fxempire.com/news/article/u-s-nft-trademark-filings-soared-400x-since-2021-902155

4 Justinas Baltrusaitis. U.S. NFT trademarks applications skyrocketed 400x in 2021 with 15 registrations daily in 2022. Available at: https://finbold.com/-s-nft-trademarks-applications-skyrocketed-400x-in-2021-with-15-registrations-daily-in-2022/

5 Hermes Complaint, 1. Available at: URL:

https://www.ledgerinsights.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/MetaBirkins-Hermes-v-Rothschild.pdf

6Agence France-Presse, Hermès suing American artist over NFTs inspired by its Birkin bags. Jan 22, 2022. Available at: URL: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/jan/22/hermes-suing-american-artist-over-nfts-of-its-birkin-bags#:~:text=French%20luxury%20group%20Herm%C3%A8s%20has,but%20ownership%20cannot%20be%20forged.

7Nike, Inc. v. StockX. Available at: URL: https://dockets.justia.com/docket/new-york/nysdce/1:2022cv00983/574411

8Nike Complaint, 2. Available at: https://heitnerlegal.com/wp-content/uploads/Nike-v-StockX.pdf

StockX’s Vault NFTs by creating the false and misleading impression StockX’s Vault NFTs are produced by, authorized by, or otherwise associated with Nike)

9 Morgan Stanley v. Joseph Masci. Available at: https://www.adrforum.com/domaindecisions/1940938.htm

10 WhatsApp, LLC v. Domain Admin, Isimtescil.net / Whoisprotection.biz / Mohammed Alkurdy, Evan Digital Technology Group. Available at: https://www.wipo.int/amc/en/domains/search/text.jsp?case=D2021-2329

Raphael

As the article mentioned, NFTs are a relatively new digital concept in Intellectual Property, especially in the legal aspect. Because it is a new legal concept, many digital businesses and lawyers will be awaiting the decisions from Hermes v. Rothschild and Nike, Inc. v. StockX. These decisions will become persuasive legal authorities and guide businesses that create NFTs. In these cases, one interesting aspect is the First Amendment protection argument raised by Rothschild and potentially raised by StockX.

More precisely, this First Amendment argument, known as the Rogers test, stems from a 1989 Second Circuit Case in Rogers v. Grimaldi. In this case, the court held that in preventing a First Amendment right intrusion, courts should balance the public interest in avoiding confusion against the public interest in free expression when deciding trademark infringement in an artistic context. As the court emphasized, the key element is whether the infringement misled the public. However, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, in Twin Peaks Prods. v. Publ’ns Int’l, Ltd., clarified and held that the infringement must present a compelling case of the likelihood of confusion to defeat a First Amendment claim. Moreover, although Rogers v. Grimaldi involved the use of celebrity names, courts have expanded the holding to other areas of Intellectual Property.

Applying the court’s reasoning, I believe the court should deny Rothschild’s First Amendment claim. Rothschild claims that these METABIRKIN bags are virtual artworks, and because the First Amendment protects artistic expressions, the court should permit them to use these NFTs. However, applying the Rogers test, I believe that a person who sees these METABIRKIN NFTs will believe that these artistic works are associated with Hermès. Hermès is a popular designer brand, and by its nature, will attract many customers. In fact, there have been several reports that customers believed that Hermès created these NFTs. Although Rothschild claims that he is not “creating or selling fake Birkin bags,” these NFTs are virtual Hermès handbags, which Rothschild is economically benefitting from.

Similarly, if raised, the court should deny StockX’s First Amendment claim. The NFTs, sold by StockX, contain Nike’s goodwill. Again, applying the Rogers test, customers will believe that these NFTs belong to Nike, primarily because StockX is known for selling authentic brands. Even worse here is that StockX is selling these NFTs, or as they call them, “investible digital brands,” at heavily high prices. Like Hermès, Nike is a very popular brand, and Nike’s goodwill will attract individuals to purchase these NFTs, thinking that Nike owns them.

In conclusion, both cases present an accurate example of the likelihood of confusion. Although these NFTs are virtual, current Intellectual Property laws should apply. Businesses should not be able to use the First Amendment as a way to rip off other businesses. Artistic works should be original. If courts decide to accept the First Amendment protection raised by Rothschild and StockX, it will incentivize businesses to steal ideas, change the name and sell it as NFTs. Here, Rothschild called the NFTs “investible digital assets,” and Rothschild substituted Birkin for “METABIRKIN.” Courts should not permit businesses to circumvent originality this way.

Daniella

The author brings up a central point that if you mint a NFT for just a digital asset that contains material or trademarks for which you do not own or have a legal permission to use, you may be responsible for infringing on the intellectual property of a third party. If you do not possess the appropriate rights to the intellectual property utilized in your NFT, you do not have the authority to give your token to a buyer. If you misrepresent the rights being transferred in conjunction with the sale of your NFT, you may be liable for further claims. Even inadvertently, exchanges or platforms that sell or display digital assets including third-party copyrights or trademarks may risk IP claims.

The United States Patent and Trademark Office classifies trademarks according to specific international “classes” of products and services. The majority of these “conventional” commodities and services do not encompass digital goods and services in the metaverse or NFTs. Consequently, it is crucial for firms to consider registering trademark applications for their goods/services in the right classifications.

Existing trademark registrations for physical items may encompass digital commodities in the metaverse, although there are presently no applicable statutes or case law governing this. If your firm is contemplating expansion into the metaverse or NFTs, it might be prudent to file for applicable trademarks to strengthen its protection.

Another complication that occurs as a result of the NFTs involves licensing rights. With NFTs, ownership and license rights are fundamental considerations. Typically, the purchaser owns the token but may only obtain a license to the underlying asset. Typically, the asset’s originator will maintain copyright. There are a variety of licensing conditions available, ranging from personal and non-commercial rights to extensive commercialization rights. Regardless of the chosen business model, the rights provided to the customer must be disclosed clearly and precisely in both marketing messages and licensing conditions. Inaccurate marketing, such as suggesting a customer “owns” an asset for which they just have a restricted license, may give rise to a variety of legal claims and other problems. The conditions of a license should clarify rights and specify precisely what a purchaser may and may not do with their purchase. To establish a valid contract, it is also vital to ensure that there is affirmative acceptance.