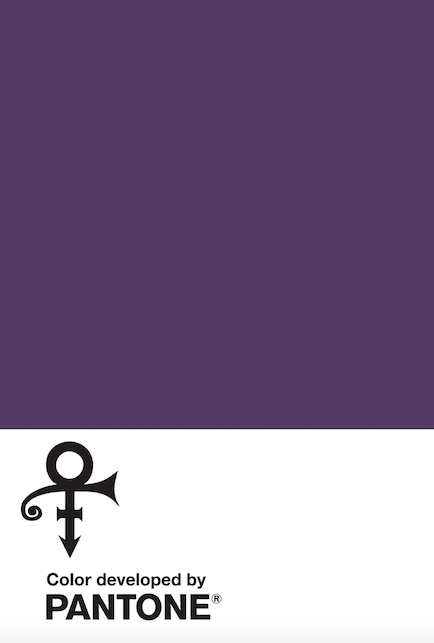

In October 2018, Paisley Park Enterprises filed an application with the USPTO (U.S. Patent and Trademark Office) for the registration of a color mark for music, live performance, and museum-related uses [1]. Paisley Park Enterprises is known for being decedent Prince Rogers Nelson’s company. In August 2017, the Prince Estate and Pantone created a purple color called “Love Symbol #2” to represent Prince [2]. The Pantone Matching system is useful to define particular shades of color, and to ensure a consistent use of the same color for one company [3].

In 1985, U.S. courts held that colors could be protected under trademark law [4]. Owens-Corning was the first company in the U.S. to hold a color mark. The fact that colors can be protected by a trademark is a natural expansion of trademark law since trademark may protect words, logos, sounds, designs, smells, and other designations [5].

To be protectible under trademark law, a mark has to be distinctive. A mark can be inherently distinctive if that mark is fanciful (an example would be a made-up or invented word, such as Exxon), arbitrary (a mark having no relationship with the goods or services being sold, for example Apple for computers), or suggestive (it requires imagination from the consumer to reach a conclusion as to the nature of the goods or services, for example Mustang for cars). If a mark is descriptive, it is not inherently distinctive and a showing of secondary meaning is required in order to be protectible. In the Qualitex case, the U.S. Supreme Court held that colors could be distinctive and protected under trademark law, but the court specified that a color can never be inherently distinctive. Since a color cannot be inherently distinctive, the applicant for a color mark is always required to show secondary meaning [6]. To establish secondary meaning, an applicant must show that the consumers associate the mark to the source of the product or services, and not to the products or services themselves [7]. In other words, the applicant must show that the mark is a source identifier.

The secondary meaning requirement may be justified by the argument that the number of possible colors to be used by competitors could be greatly diminished if the courts and the USPTO were to give trademark rights too easily on trademark applications for color marks. A requirement of secondary meaning limits that possible depletion of the possible colors to be used. Courts may be reluctant to give trademark protection for color marks too lightly, since in some instances there might be underlying reasons behind the use of certain colors. An example is the color orange for safety-related companies and products. Another possible issue is the idea of shade confusion, courts may have difficulties in determining which colors are similar enough to constitute a trademark infringement, and which are not.

Functionality is a bar to trademark protection. If a mark is functional, it can not be protected under trademark law, even if the mark holder would have been able to show secondary meaning. The courts use two tests in order to determine whether a mark is functional or not. A mark is functional under the first test (known as the Qualitex test) if the exclusive use of the mark would put competitors at a significant non-reputation-related disadvantage [8]. Under the second test (the Inwood test), a feature is functional if it is essential to the use or purpose of the article, or if it affects the article’s cost or quality [9]. To be non-functional, a mark has to be non-functional under both tests. The concept of aesthetic functionality, absent from the statutes but recognized by virtually every court in the U.S., is also a possible barrier to the registration of a color mark. This concept applies in the case of features which have no functional utility, but that consumers want, often for aesthetic reasons. In most cases relating to aesthetic functionality, the first test of functionality is satisfied as an exclusive use would put competitors at a significant non-reputation-related disadvantage, and the mark is then deemed functional. A color mark may be functional in some instances according to this aesthetic functionality concept.

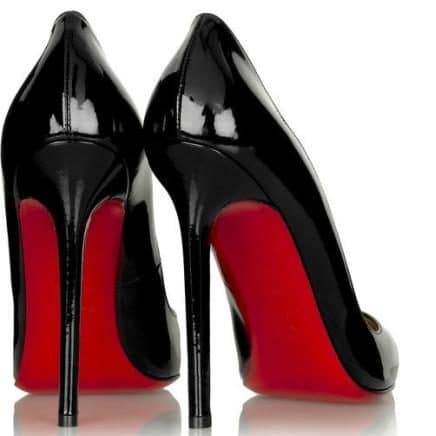

In a case opposing Christian Louboutin to Yves Saint Laurent, courts held the trademark protection on Christian Louboutin’s red sole to be enforceable, but that this protection only covered shoes when the red sole contrasted with the upper of the shoe [10]. That protection is thus limited and does not extend to the manufacture and sale of monochrome red shoes with a red sole, such as the red Yves Saint Laurent’s shoe at issue. This decision allowed Louboutin to benefit from trademark protection on its red sole without putting its competitors at a significant non-reputation-related disadvantage.

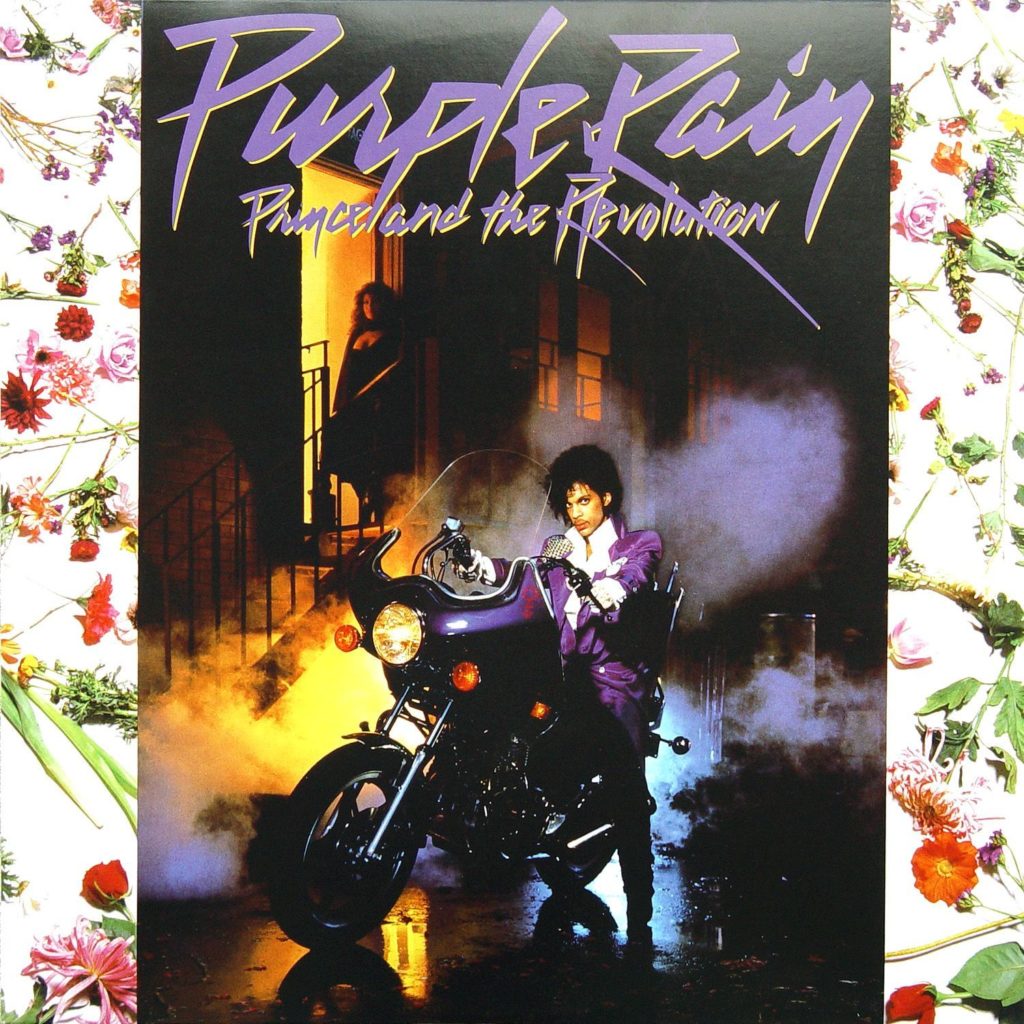

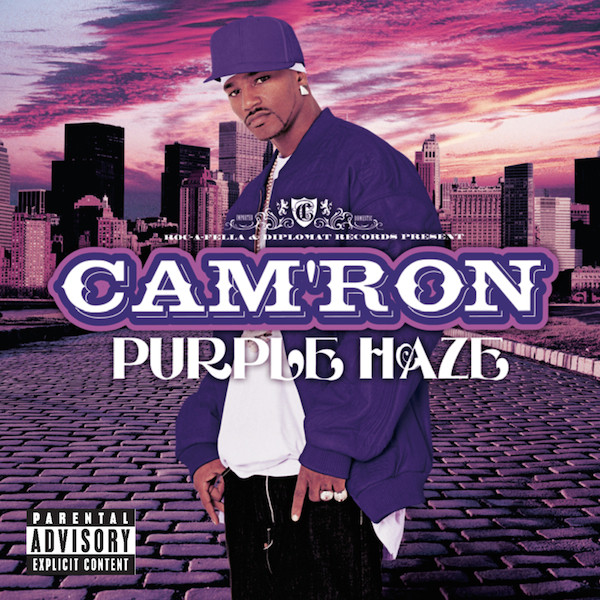

The USPTO refused to register Paisley Park Enterprises’ “Love Symbol #2” mark because consumers do not perceive this color as a source identifier according to the USPTO. The USPTO noted that album covers from other artists such as Cam’ron and Kanye West also included the use of the color purple, and that the purple color was not distinctive of Paisley Park Enterprises’ products and services as it is a commonly used color in the sale of products and services in the same class. [11]

Color is often used as a source identifier by companies. Tiffany’s Robin’s Egg blue color, which is used on their boxes, is protected by a trademark, the Tiffany Blue hue has been held to be distinctive through an acquired secondary meaning. UPS also registered its brown color as a trademark [12]. Paisley Park Enterprises may try to show that the particular purple color they are trying to register serves as a source identifier, and they may argue that consumers associate this purple color to Prince. If Paisley Park Enterprises manages to show secondary meaning, the USPTO will be likely to accept the registration of the “Love Symbol #2” color mark.

[1] http://www.thefashionlaw.com/home/princes-estate-is-seeking-federal-trademark-protection-for-his-purple-pantone-hue

[2] https://www.pantone.com/about/press-releases/2017/the-prince-estate-and-pantone-unveil-love-symbol-number-2

[3] https://www.ipwatchdog.com/2018/07/14/can-you-trademark-a-color/id=99237/

[4] In re Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corp., 774 F.2d 1116 (Fed. Cir. 1985)

[5] Restatement of the Law (Third), Unfair Competition : §9 Definitions of TM and service mark

[6] Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co. Inc., 514 U.S. 159 (1995)

[7] https://tmep.uspto.gov/RDMS/TMEP/current#/current/TMEP-1200d1e10316.html

[8] Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co. Inc., 514 U.S. 159 (1995)

[9] Inwood Laboratories Inc. v. Ives Laboratories, Inc., 456 U.S. 844 (1982)

[10] Christian Louboutin, SA v. Yves St. Laurent America Holding, Inc, 709 F.3d 140 (2d Cir 2013)

[11] http://www.thefashionlaw.com/home/us-trademark-body-says-prince-was-not-the-only-musician-to-make-use-of-the-color-purple

[12] https://www.ups.com/media/en/trademarks.pdf

Mary

My previous career was in the paint industry, so colors were a primary focus of my life for many years. I never really considered whether colors could be trademarked before I read this article, even though I spent a lot of time creating my own formulas for paint colors. The tint machine, which is used to add colorants to tint the neutral paint base, has a library of standardized colorant formulas for each one of the company’s paint colors. Any measurements that are manually entered or scanned in with a color reader are considered “custom” since they deviate from the preset standards, and these custom formulas are quite common. Customers would frequently ask if their paint could be matched to an existing color, and their reference material would vary from competitor color swatches, to household décor (such as vases or curtains or pillowcases), to sports team colors, and their requests would be fulfilled.

After reading this article, I was thinking about whether there could be potential disputes for recreating a color that is sold in association with a brand, and no, there would not be in the instances of competitor and household décor colors since there are not trademarks in either. The sheer volume of different tones involved in paint and décor would make it nearly impossible for the average consumer to properly identify the source. There would definitely be “shade confusion” in a court. Sports team colors, however, are trademarked in some cases, like the NFL. But then again, home improvement and major professional sports leagues are clearly different trades, and there is an extremely low likelihood that there would be confusion over whether your kitchen’s accent wall was a product of the NFL.

Additionally, I agree that the doctrine of aesthetic functionality does seem as if it would be an additional barrier in trademarking colors as well as other design features. If an aesthetic feature does not have a utilitarian function, but the feature is so coveted by consumers that it creates a competitive advantage for the party claiming the feature, there is an aesthetic function because competition in the market would be at a disadvantage without access to the feature. There seems to be a very thin and blurry line between aesthetic functionality and well-executed branding, at least it certainly seems that way in the Louboutin case. The court found that the red sole was not functional, as it is a rather restricted feature and it does not hinder competitors’ artistic expression. See Christian Louboutin, SA v. Yves St. Laurent America Holding, Inc., 709 F.3d 140 (2d Cir 2013). However, Yves Saint Laurent’s use of the red sole had a specific, tangible reason, which was to create a monochromatic look, and this factor seems to lean in favor of functionality. Arguably, the red sole is an aesthetic component that functions as completing a design objective, but ultimately, consumers desire the red sole because it is so closely associated with Louboutin and the implied prestige, and this tilts the scale in favor of the absence of functionality. All-in-all, I believe that the application of the doctrine of aesthetic functionality will generally impede individuals who wish to trademark a color.

Jonathan

The Qualitex [1] case shows how color can be trademarked in a specific circumstance. In Qualitex, the Supreme Court held that colors can be trademarked if distinctive or, if not distinctive, if it can demonstrate “secondary meaning”. The Court held that a color could never be inherently distinctive so that leaves only the avenue of “secondary meaning” for an applicant to obtain a color trademark. A mark has “secondary meaning” if there is “mental association . . . between the alleged mark and a single source of the product.” [2] Essentially, where a color is widely recognized as symbolic of the product, it satisfies this “secondary meaning” requirement. After reading this, it seems like a home run for Paisley Park Enterprises’ attempt to trademark the color formerly known as purple “Love Symbol #2” which is widely recognized as synonymous with Prince’s branding, however there are wider considerations that must be taken into account.

The Qualitex case concerned the color mark on dry cleaning “press pads” where the color wasn’t integral to the functionality of the pads, they would function as dry cleaning “press pads” no matter what color they were (although it was recognized that a color was needed to obscure stains). The Court distinguished this from circumstances where the color would be integral to the functionality of the product, for example, the color of medicinal pills to denote the type of medicine. In those cases, a color-only trademark would not be granted as it would allow the owner of the trademark exclusive use of a color in a domain where the color is a functional part of the product. This is called the doctrine of functionality and serves to maintain competition in the market for the above reason, also partially under the “color depletion” theory as argued by Defendants in Qualitex. The color depletion theory put forth by Defendants argued that granting color-only trademarks reduced the amount of colors available to competitors in that domain, again reducing competition, however, it was deemed unpersuasive by the Court.

The creation and trademark application of “Love Symbol #2” also raises the issue of trademarking colors and shade confusion. The concern here is the exactitude desired by the law of trademark in granting applications.

The Courts are accustomed to dealing with far more exact concepts when considering trademarks. Words are easy to analyze as one word is quite obviously different to another word whereas color exists on a spectrum and while there are generic descriptions of colors (red, blue, green, yellow, orange) there are also thousands upon thousands of varying shades. Perception of color can change depending on light or when contrasted next to another color, one color can be said to be different shades depending on the light available. While there exists a standardized color spectrum, many manufacturers utilize their own system and name colors as they choose which creates difficulty for a centralized body attempting to grant and record trademarks. How does the body differentiate between “Love Symbol #2” and hypothetical A Corporation’s “Magnificent Light Indigo”?

What can be surmised from the above is that color marks are considered inside of their industry and against products of the same or similar function. Paisley Park Enterprises’ trademark application for “Love Symbol #2” does not fall neatly into an industry or on to a product, it is a color associated with Prince’s “branding”. It was inspired by the color of his iconic piano, as his motorbike, album cover and clothing and with that comes the issue. These iconic Prince pieces are spread across a very wide variety of products so granting a color-only trademark would grant Paisley Park Enterprises exclusive use of this purple color in far more areas than it operates, if it can be said to operate in an area at all.

So, while “Love Symbol #2” might be recognized widely as synonymous with Prince, it is not contained within one sphere of industry where a color-only trademark would be upheld.

[1] Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co., Inc., 514 U.S. 159 (1995).

[2] 2 J. Thomas McCarthy, McCarthy On Trademarks And Unfair Competition § 15:5 (4th ed. 2010).

Sean

Color trademark is a very interesting topic because unlike other marks, color cannot be distinguished from other service marks like word mark if it is used in different circumstances. In re: Thrifty, Inc., 274 F.3d 1349 (Fed. Cir. 2001). In other words, color marks are not distinctive but descriptive. As the article says, in order for the color mark to be protected, it needs to establish secondary meaning by showing “that the consumers associate the mark to the source of the product or services.”

My first response to this establishing secondary meaning was this standard could be very arbitrary because I felt like color can be used by anyone for any purposes. However, in the case of Louboutin and Tiffany, I can understand why the court recognized the color mark. I think the best way to show that the color has secondary meaning is through how famous the brand is and how long has the brand been using that mark. Not only are Louboutin and Tiffany world famous brands that almost everyone knows, or at least heard of the name, but their products are unique as well. Even though color marks can never be inherently distinctive, companies like Louboutin and Tiffany used their color mark enough to acquire distinctiveness. For example, Tiffany’s Robin’s Egg blue color (aka the Tiffany Blue), is so famous that the customer expects to get their jewelry in the Tiffany Blue box.

Louboutin’s red soles can be understood in the same way. Customers who buy Louboutin shoes would expect to have red sole on their shoes. However, the 2nd circuit limited Louboutin’s color mark only to “shoes when the red sole contrasted with the upper of the shoe. That protection is thus limited and does not extend to the manufacture and sale of monochrome red shoes with a red sole, such as the red Yves Saint Laurent’s shoe at issue.” This was to limit the aesthetic functionality of the Louboutin’s red sole design. Of course, the customers would expect red sole on Louboutin’s shoes, but this would be functional if it bans Yves Saint Laurent’s monochrome red shoes with a red sole because this puts Yves Saint Laurent at a significant non-reputation-related disadvantage by not selling their shoes. I think this case well represents the hardship of the court to determine whether the color mark is functional. By limiting Louboutin’s red sole color mark only when the red sole contrasted with the upper of the shoe, the court protected both Louboutin’s color mark and Yves Saint Laurent’s monochrome red shoe.

In Prince’s case, USPTO’s refusal to register “Love Symbol #2” makes perfect sense because Love Symbol #2 is arguably functional. Paisley Park Enterprises may have created their new purple color for Prince, but unlike Tiffany, they did not have enough time to make the public associate their Love Symbol #2 with Prince. If they waited more years and constantly use the Love Symbol #2 for all of Prince’s products, then the decision might have been different. However, Paisley Park Enterprises failed to show that Love Symbol #2 has a secondary meaning by showing that the “consumers associate the mark to the source of the product or service,” Love Symbol #2 is thus functional and cannot be protected because the exclusive use of Love Symbol #2 would put competitors at a significant non-reputation-related disadvantage.

MJ

According to the article, the color has been used and associated with different singers, entities and brands. Also, Prince did not use this particular shade of purple on all his merchandise or albums. The merchandise uses different shades of purple and his other albums use orange, white, yellow, and red shades. Most of the time, purple accompanies the Love Symbol mark which is already owned and used by the Estate. However, as in Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co., Inc., 514 U.S. 159 (1995), Love Symbol #2 “identifies and distinguishes” any merchandise or product related to Prince and his music. I am convinced the Prince Estate will successfully patent the color alone.

Qualitex allows trademarking color alone if the color “identifies or distinguishes the seller’s goods,” not functional, and “developed a secondary meaning.” Qualitex at 159. Secondary meaning attaches when “the primary significance of a product feature or term is to identify the source of the product rather than the product itself.” Inwood Laboratories, Inc. v. Ives Laboratories, Inc., 456 U.S. 844, 851 n.11 (1982). Based on these precedents decided in the context of the Trademark or Lanham Act of 1946, the particular shade of purple must single-handedly identify and distinguish all products associated with Prince. The customer must also be able to directly associate the color with a source. In other words, when the customer sees the Love Symbol #2 purple, he or she has to directly know or recognize that the color is a symbol for Prince.

Since the Purple Rain album and movie gained widespread popularity, Prince became closely associated with the color. He gave meaning to the color and the color carried his message. He also used the color in his concerts, music videos, stage clothes and even played a purple guitar. When he passed away, the color represented his legacy in the music industry. The color has sufficient history with Prince so that both fans and non-fans immediately associate the two. The color does not simply remind you of his products or music, but of the artist Prince and his company. The color has become a symbol for Prince. Moreover, the color is not functional. Love Symbol #2 is neither “essential to the use or purpose of an article” nor “affects cost or quality of an article.” See Inwood Laboratories, Inc., at 850 n.10. Artists in the same industry would not suffer “non-reputation related disadvantage” from inability to use the particular color. Id. Trademarking Love Symbol #2 will not inhibit competition or give competitive disadvantage to others in the market. There are plenty of alternative colors that other participants in the market can use for their products.

At the least, the Prince Estate may achieve a “trade dress” protection where the color is trademarked with a specific design under § 43(a) of the Lanham Act, or a limited trademark. See 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a) (1988 ed., Supp. V); Qualitex at 173. In the Christian Louboutin case cited in the article, the court granted Louboutin limited trademark to shoes with red soles used with a contrasting color. See Christian Louboutin, SA v. Yves St. Laurent America Holding, Inc., 709 F.3d 140 (2d Cir. 2013). The court and/or the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) may easily grant the Prince Estate ownership of Love Symbol #2 when attached with the Love Symbol mark of Prince. Alternatively, the court could limit others from using Love Symbol #2 with black in albums or merchandise as commonly done by Prince.

Although the Lanham Act and trademark precedents are favorable to the Prince Estate, the Lanham Act allowing ownership of a color is concerning. Evident from the precedents, USPTO mainly intended trademarking color to ensure ownership and competitive benefits for entities such as products and brands. The color is not trademarked by an individual artist but by brands that have a longer history and common association with their product and its color. However, Prince’s Love Symbol #2 case offers a glimpse of the Lanham Act’s eventual expansion into other industries such as art and technology. The possibility of trademarking color opened up a floodgate of difficult legal questions and issues, especially since color is based on visual perception and has limited options.

I agree with some of respondent Jacobson Products Co.’s arguments to the court in Qualitex. Jacobson addressed the concern that distinguishing color will cause confusion and uncertainty in court disputes. See Qualitex at 167. Also, available colors will eventually run out if each and one of them begins to be owned by private entities. Id. at 168. Even if courts have extensive experience with answering and resolving difficult questions about similar words or phrases or colors with designs, it all comes down to discretion and perspective in the end. See id.

Answering Jacobson’s question about the limited supply of colors, the court suggests using the functionality test as a second measure. However, as the court acknowledges, even functionality is not an absolute bar to trademarking a color. Id. at 165. When the color does not necessarily “make a product more desirable,” functionality loses power because it does not serve “a significant function” for the product. Id. at 165, 166. So then, what do we do when we actually run out of colors?

The somewhat vague language of the Lanham Act has given the freedom to argue and the right to claim ownership of ideas and products borne out of those ideas. Unfortunately, especially for non-tangible subjects such as color, determining trademark ownership will continue to put courts in a conundrum. More than ever, legal precedents in trademark law will be highly important and essential for courts to reach a fair and practical decision.