by Augustus Balasubramaniam, Esq.

Contracts Overview

In New York, for a legally enforceable agreement to exist at contract, the Plaintiff must establish an offer, acceptance of that offer, consideration moving between the parties, mutual assent, and intent to be bound. See Kwalchuk v. Stroup, 61 A.D.3d 118, 121 (1st Dep’t 2009). An Offer is defined as “…the manifestation of willingness to enter into a bargain, so made as to justify another person in understanding that his assent to that bargain is invited and will conclude it” (see Restatement (Second) of Contracts §24). “…(I)t must create a reasonable understanding in the offeree that the offeree has the power to create a contract by simply manifesting an assent to the offer…” See Dr. John E. Murray, Jr., Corbin on Contracts (Desk Edition 2015) § 1.05.[2] Acceptance of an Offer is a “…manifestation of assent to the terms thereof made by the offeree in a manner invited or required by the offer…” See Restatement (Second) of Contracts §50 (1). Acceptance can be by performance or a promise to perform[1], if the offer invited such mode of acceptance. Acceptance must be a voluntary act on the part of the offeree. Consideration is the bargained for exchange moving between the parties.[2] Generally, in an arms length bargain, the Courts will not inquire into the adequacy of consideration[3]. However, the bargained for exchange must move between the parties simultaneously, meaning generally, consideration must not be something done in the past, or something the party is already legally obligated to do[4]. Lastly, for an enforceable agreement to exist, it must meet the requirements of the Statute of Frauds.[5]

Breach of Contract

A Breach of contract occurs, when performance of the contractual obligations is due, but one or more of the parties to that contract fails to perform their obligations. “…[A] contract is not breached until the time set for performance has expired…” See Cole v. Macklowe, 64 A.D.3d 480, 480 [1st Dep’t 2009]. Alternatively, anytime before performance is due, if a party makes a clear, and unambiguous statement of an intent not to perform, or from that party’s conduct, it can be reasonably deduced that the party does not intend to perform, there is anticipatory breach of the contract. The party to whom performance is due may have recourse to remedies at this point in time, not withstanding performance is due sometime in the future.[6]

Remedies

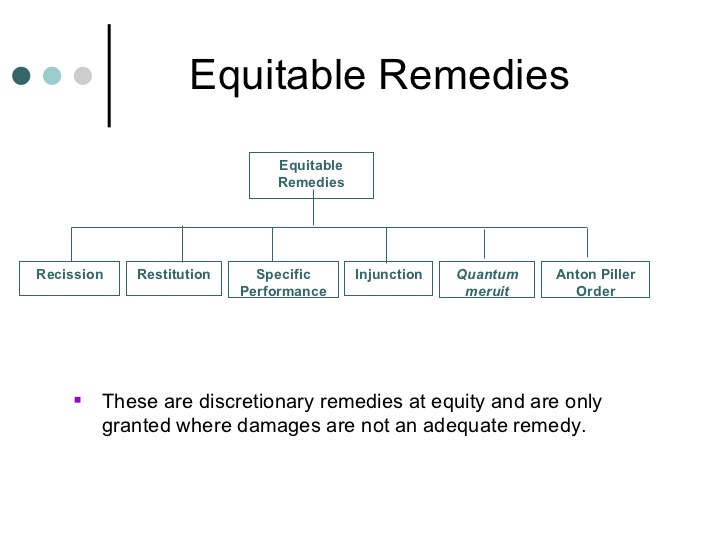

Generally, a party that suffers a loss due to a breach of contract may sue for remedies under law or equity. The most common type of remedy under the law would be damages. Providing it is foreseeable, the law will afford the aggrieved party monetary damages, the measure generally, being to put the aggrieved party in the position as if the contract had taken place. See Restatement (Second) of Contracts §§ 344-352 et al. If, on the other hand, the facts of the case dictate that damages are not feasible, equity may step in to afford what is known as an equitable remedy such as specific performance or injunction. This is especially so in real property contracts, or contracts where the subject matter of the contract is a unique good. It should be noted however that specific performance will not be available to compel individual performance of a contract due to constitutional issues that arises, specifically the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, thus varying somewhat from other common law jurisdictions. See Vanderbilt University v. DiNardo, 174 F.3d 751 (6th Cir. 1999).

Implications for Equitable Remedies in Day-to-Day Practice

It is not uncommon, when an attorney drafts a pleading for a breach of contract case, to see a wrongly chosen remedy, which sometimes could be fatal to the litigation at issue. It is essential therefore that attorneys ensure the remedy chosen fit the elements of the remedy they seek, and which in turn applies to the facts of the case. This is especially true when attorneys are faced with a situation in their clients’ cases where there is no clear remedy in law. Courts are varied in their approach to the grant of equitable remedies for breach of contract. While, generally, it could be agreed the courts will look at ‘all the circumstances of the case’, and if it is ‘just and equitable’ to grant equitable relief in the case, what that means in practice will vary greatly. Drafters of contracts include what is known as “equitable relief clauses” in contracts in the hopes, at least to some extent, to try to limit the uncertainty surrounding the grant of equitable relief by the courts. Some jurisdictions such as Delaware, interpret equitable relief clauses in contracts as giving rise to a presumption of irreparable harm, a factor to be established by the plaintiff in order to succeed in getting equitable relief from the courts. See Gildor v. Optical Sols., Inc., No. 1416-N, 2006 WL 4782348 (Del. Ch. June 5, 2006). Other jurisdictions, including The Federal Courts, on the other hand, place very little-to-no weight to these equitable relief clauses in contracts. See La Jolla Cove Inv’rs, Inc. v. GoConnect Ltd., No. 11CV1907 JLS JMA, 2012 WL 1580995 (S.D. Cal. May 4, 2012). See also Smith, Bucklin & Assocs., Inc. v. Sonntag, 83 F.3d 476, 478 (D.C. Cir. 1996). Our own courts here in New York have taken the middle ground in cases that have come before them in relation to the equitable relief clauses in contracts. The courts have shown willingness to consider the existence of the said clauses in their overall analysis of whether equitable relief should be granted. See Imprimis Investors LLC v. Indus. Imaging Corp., QDS 22701503, 2008 N.Y. Misc. LEXIS 7384, at *16–17 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Sept. 7, 2008). See also Gramercy Warehouse Funding I LLC v. Colfin JIH Funding LLC, No. 11 CIV. 9715 KBF, 2012 WL 75431 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 6, 2012).

Is breach of contract illegal?

Breach of contract itself, per se, is not illegal in New York. A breach of contract occurs when one party fails to fulfill their obligations under a legally binding agreement without a valid excuse. However, when a breach of contract happens, the non-breaching party has legal remedies available to them. They can sue the breaching party for damages, specific performance (forcing the breaching party to fulfill their obligations), or other appropriate remedies as specified in the contract or allowed by law. Legal consequences arise from the failure to fulfill contractual obligations, rather than the breach itself being illegal. It’s important to consult with a qualified attorney for specific legal advice related to contract disputes in New York or any other jurisdiction.

Bottom line is, when dealing with breach of contract cases seeking equitable relief; it is prudent for the practitioner to ensure airtight arguments to further their client’s case. The old English saying from some 350 years ago, which articulated a common complaint amongst the legal practitioners of yesteryear, to some extent, holds true even today…‘Equity is a roguish thing. For Law we have a measure, know what to trust to; Equity is according to the conscience of him that is Chancellor, and as that is larger or narrower, so is Equity. ‘T is all one as if they should make the standard for the measure we call a “foot” a Chancellor’s foot; what an uncertain measure would this be! One Chancellor has a long foot, another a short foot, a third an indifferent foot. ‘T is the same thing in the Chancellor’s conscience. See Edward Fry, Life of John Selden, in “Table Talk of John Selden” (Fredrik Pollock edition, 1927) at page 177.

[1] See Restatement (Second) Contracts §§50 (2), (3), 53-54.

[2] See Restatement (Second) Contracts §71.

[3] See Moezinia v. Ashkenazi, 136 A.D.3d 988 [2d Dep’t 2016].

[4] See Braka v. Travel Assistance Intern., 25 A.D.3d 456 [1st Dep’t 2006].

[5] Contracts for goods of $500 and more are covered by the Uniform Commercial Code which mirrors the Statute of fraud provisions.

[6] See O’Connor v. Sleasman, 37 A.D.3d 954, 956 [3d Dep’t 2007].

Richard Ellis

Expert analysis, and well written.

Rayan

Equitable remedies are awarded subject to the court’s discretion and used when damages are an inadequate remedy. Therefore, it is vital for parties to address the inadequacy of damages by understanding the mechanism for damages calculation and, ultimately, incorporating into their contracts. Under §344 of the Restatement (Second) of Contracts (‘Purposes of Remedies’), damages shall be calculated as per the below mechanisms:

Expectation interest

The court will calculate monetary damages to put the Plaintiff in a position as if the contract was fully performed. For example, the Plaintiff provided a service to the defaulting Defendant worth $100,000, expectation damages would entitle the Plaintiff to claim up to $100,000 thereby putting the Plaintiff in a position as if the contract was performed. Under §347 of the Restatement (Second) of Contracts (‘Measure of Damages in General’), expectation damages allow the Plaintiff to also claim incidental or consequential losses caused by the Defendant’s breach. For example, if the Plaintiff hired a replacement to complete the Defendant’s work or procured security guards to safeguard the Defendant’s incomplete work, any increased costs incurred can be claimed provided that such costs are reasonably certain. Where it becomes more problematic is in the relation of lost profits suffered as result of the breach. Sections 351 – 353 of the Restatement (Second) of Contracts provide some guidance by restricting damages to foreseeable and probable loss that must be substantiated by reasonably certain evidence. Therefore, loss of profits can be claimed as evidenced by past accounts rather than projected targets. To promote contractual certainty, many parties opt to exclude consequential loss such as loss of profits or loss of goodwill/reputation by incorporating a limitation of damages clause. Additionally, parties may cap liability to the contract’s value. Therefore, based on the above scenario, liability would be capped to $100,000. However, courts may strike down this clause if it does not expressly allow parties to recover additional damages exceeding the contractual value if attributing loss arises out of the Defendant’s tortious actions (e.g., intentional or fraudulent misrepresentation).

Reliance interest

The court will calculate monetary damages to put the Plaintiff in a position before the contract was made. For example, the Plaintiff paid an advance or deposit as part of the Defendant’s catering services. In the event that the service becomes unavailable (e.g., defaulting Defendant doesn’t possess license or items become unavailable), the Plaintiff can claim any advance payments since the payment was in made in reliance of the legal execution of the catering services contract. Reliance damages are usually a viable option when expectation damages are unavailable. This occurs in various instances including when the cost of performance (the expectation interest) is unforeseeable, difficult to measure or unreasonably exceeds the market value of the performance (i.e., cost of a replacement service). Additionally, if the Plaintiff did not take reasonable measures to mitigate his losses (e.g., failing to secure a construction site resulting in damages substantial increasing the Defendant’s cost of performance), reliance damages would be deemed as the appropriate option.

Restitutionary interest

A Plaintiff can elect to request restitutionary damages based on the benefits gained by Defendant. For example, Plaintiff was paid an advance equal to 10% of the contract’s value to build a swimming pool and completed 90% of the construction. The Defendant terminates the service contract without justification since he procured a third party to complete the final adjustments at a substantial reduced price. Incorporation of a swimming pool in the Defendant’s property increased the value of his property by $30,000. The Plaintiff can claim expectation damages for the remaining value of the contract or claim restitutionary damages for the increased value of the property. Restitutionary damages are a viable option when selection of an expectation damages would adversely impact the Plaintiff. Therefore, based on the above, if the remaining payment is less than $30,000, it would be advantageous for the Plaintiff to claim restitutionary damages.

Liquidated damages

Under §344 of the Restatement (Second) of Contracts (‘Liquidated Damages and Penalties’), Parties can be incorporated in a contract to calculate actual harm suffered by the Plaintiff provided such clause is reasonable in relation to the actual harm suffered and not used as a penalty. Liquidated damages are best utilized in scenarios where timely performance of the service contract is essential. For example, in a lease, the Defendant is charged for each day where rent remains unpaid. To ensure that the liquidated damages clause is proportionate to the actual harm suffered, parties set a cap on the total recoverable amount e.g. for each day rent is delayed, a charge of $10 shall apply and cumulative liability shall not exceed $50. Many parties opt to use liquidated damages since it simplifies damages calculation and usually provides quick recourse without the need for judicial intervention. Calculating and proving actual damages (e.g., consequential damages and benefits incurred under a restitutionary interest) can be both difficult and time consuming. Additionally, a defaulting party is able to ascertain its potential liability and take the appropriate steps (e.g., deduct the payable liquidated damages from their invoices).

It is vital that parties treat their contracts as a tool to establish clear lines of responsibilities and avoid subsequent misunderstanding.

Chris Fry

Very well written and very informative. I would have to agree that the emphasis should be on appropriate remedies

Shuwen

This well written article provided me with a review of some important points in both Property and Contracts, as well as gave me a general picture of what does equitable remedies look like in New York. Equitable remedy is within a court’s discretion, and as the article has discussed, it includes specific performance, injunction, recission (cancellation of the contract by mutual decision or by court), etc. Courts have the equitable power to decide the appropriate type of relief.

The previous post from Rayan has addressed the mechanism for damages calculation and the 3 types of damage awards, so I will not discuss all of them in detail here. Specifically, the goal of expectation damage is to give a plaintiff the benefit that he or she was expecting under the performance of a contract, e.g. awarding the money value of performance to plaintiff or compelling defendant to render the promised performance to plaintiff (specific performance). Adding to Rayan’s discussion of expectation interest, in real estate contract, expectation damage could be the difference between the contract price of the property and the market price of it at time of breach. See Crabby’s, Inc. v. Hamilton, 244 S.W.3d 209, 217 (Mo. Ct. App. 2008). The fair market value at time of breach could be established by: (1) expert testimony, e.g. real estate appraisers or others who’re qualified by education, training, or experience, (2) contract price from property owner (may be problematic), and (3) resale price if within a reasonable period time.

It is interesting to notice the difference between English rule and American rule when the seller breaches contract. English rule states that buyer restricted to restitution of any payments made on the purchase price (e.g. earnest money), and if seller has breached in bad faith, then buyer can get expectation damages. However, American jurisprudence states that buyer can get expectation damages regardless the seller breaches the contract in good faith or bad faith.

What’s more, courts usually grant specific performance in property sale contracts in consideration of the uniqueness of each parcel of property. Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 359 provided an inadequacy-of-damages test to decide the use of specific performance for contracts. Section 359 listed several factors to determine whether damages would be adequate, for instance, how difficult it is to prove damages with reasonable certainty and/or how likely that an award of damages could not be collected successful. In Ammerman v. City Stores Co., the court ordered specific performance based on the inadequacy of damages to compensate the plaintiff for his loss of right to participate in the business of a shopping center, since there was no way to calculate damages in this case (e.g. the profit that plaintiff would have made if it opens a store in the shopping center). See 394 F.2d 950, 955-56 (D.C. Cir. 1968). The court held that it was almost impossible to substitute performance of the contract because the location of shopping center and the opportunity to have business there are unique. Id.

Moreover, specific performance usually will not be granted unless contract terms are sufficiently certain to provide a basis for an appropriate order. In addition, courts may reject granting specific performance if there is greater difficulty for the court to supervise performance that is outweighed by the importance of the remedy. See Mayor’s Jewelers, Inc. v. State of Cal. Pub. Employees’ Ret. Sys., 685 So. 2d 904, 905 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1996). Restatement (Second) of Contracts also put some limitations on the granting of specific performance. For instance, § 364(1) stated that specific performance or injunction will be refused if the contract was induced by mistake or unfair practice, and § 365 mentioned that specific performance will not be granted if it would be contrary to public policy.